Alchemy and Screen Acting

“Before doing anything, we first have to want to do it. That desire is our energising force, our motivation or e-motion. Emotion is not identical with feelings, which comprise our sensitivity and reactions to emotion. Emotion, or desire, is our motivating force - our will and energy. Every desire or emotion leads to a thought, in which we want and plan our action. Finally, we put thought into action. ”

Actions Reveal Character

At film school, my screenwriting tutor Gerry Wilson gave me advice I've never forgotten: "Stop trying to be clever. If your characters are explaining their feelings, you're doing it wrong. Show me what they do." Gerry had written films for Charles Bronson and Burt Lancaster — men who barely spoke yet communicated everything through action. His principle was simple: actions reveal character. What people do under pressure tells us who they really are.

Lawman and Chato’s Land - both screenplays by Gerry Wilson

I applied that principle to the script of my graduation film, MacHeath, which went on to win several student awards and got me my first professional job directing Brookside, Channel 4's groundbreaking Liverpool drama. This was Brookside at its peak — Sue Johnston's iconic Sheila Grant and John McArdle's Billy Corkhill going through the mill week after week. But I knew that attracting that level of talent for my own projects meant I'd need to master screenwriting as well as directing. So I kept searching for the deeper logic of story structure — something beyond the mechanical three-act formulas that worked for analysis but felt lifeless for creation. Syd Field's Screenplay told you Act One was pages 1-30, Act Two pages 30-90, Act Three pages 90-120. Useful for dissecting existing films, but I didn't find it useful in creating new ones. Stories felt more organic than that, more cyclical.

Then I stumbled on something unexpected. Browsing in Watkins bookshop off Charing Cross Road, I found The Wisdom of Shakespeare in As You Like It by Peter Dawkins. I'd already encountered the Shakespeare authorship question, which had opened my mind to the possibility that the plays contained hidden structures beyond what conventional scholarship acknowledged. Dawkins went further: he argued that Shakespeare had embedded ancient alchemical principles into his dramatic architecture — cycles of transformation that governed how the plays actually worked. I bought the book and read it in one sitting. Before I'd finished, I knew I had to meet this man.

Synchronicity intervened. Dawkins was running workshops at Shakespeare's Globe with Mark Rylance, then the theatre's Artistic Director. I bought a ticket immediately. Peter comes across as a self-effacing, mild-mannered gentle-man who is a walking encyclopedia of Western wisdom tradition. He describes himself as a philosopher, seer and geomancer, but you only grasp what he really offers when you hear him teach. Each workshop accompanied a Globe production, so we'd study the play's hidden structure by day and experience it performed that evening. I attended every workshop they ran until Rylance left the Globe to pursue what has turned out to be a spectacular screen career. I remember him humbly saying at the time that he had no idea where the work would come from. Then his screen career exploded — Wolf Hall, Spielberg, Bridge of Spies, an Oscar. Talent in action. The man is an inspiration to work with. That decade of workshops was genuinely life-changing.

Mark Rylance as Cleopatra in an all-male production of Antony and Cleopatra by Shakespeare at the Globe Theatre in London in 1999

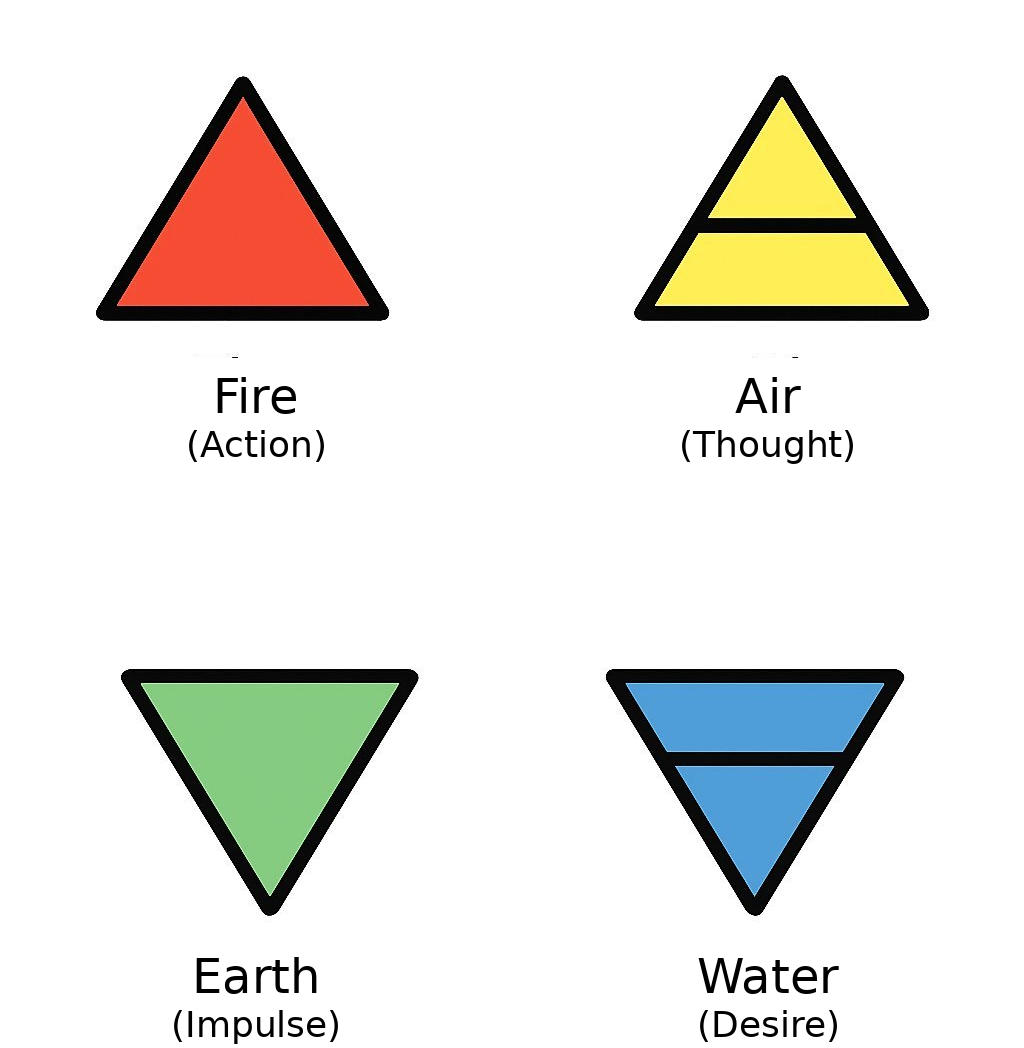

In those sessions, I grasped the practical core: the four alchemical elements — Earth, Water, Air, Fire — translated directly into psychological stages. Earth as Impulse. Water as Desire. Air as Thought. Fire as Action. This wasn't abstract symbolism. It was a map of how human beings actually process experience. Every decision we make, every action we take, follows this cycle. Dawkins used the metaphor of a burning candle: solid wax (Earth) melts to liquid (Water), evaporates to vapour (Air), ignites into flame (Fire), and finally radiates as light. That light — the fifth element, Ether — represents the raised awareness that emerges when the cycle completes. Transformation isn't just change; it produces illumination.

Here, finally, was the organic structure I'd been searching for. But I had no idea yet how useful it would prove — not only for writing, but also for something else entirely.

The Missing Mechanism

Meanwhile, my career moved from Brookside to The Bill, ITV's police procedural, pulling in eight million viewers. The casting pressure was relentless. Up to half a dozen guest roles had to be cast for each episode, which meant seeing up to forty-eight actors — eight auditioned per role. Those four-hour casting sessions had to be crammed into the mornings of the first week of a short, hectic pre-production period, where I was also location hunting, script editing, attending production meetings, and planning the shoot. The effect of all that time pressure? On average, each actor got only about 15 minutes in the audition room.

Actors would arrive at the Merton studios, collect their sides from reception, and have perhaps half an hour to prepare the material — an interrogation scene with DI Burnside (Chris Ellison), a confrontation with DS Ted Roach (Tony Scannell), a witness statement to PC Reg Hollis (Jeff Stewart). From the director's point of view, one bad casting decision could derail an entire production schedule. With three sets of episodes and three different directors shooting concurrently, any reshoots meant schedule chaos. We played it safe — familiar faces, proven performers, minimal risk.

It was a challenging system. Directors couldn't afford to take chances. Actors couldn't show their full potential in such a limited time. Everyone was doing their best, but we were all trapped by the same time pressure. And it was in that environment that I remembered Dawkins' cycle.

When an actor seemed stuck, instead of the usual "tell me about your character" — which ate up precious minutes — I'd try something different. "What's the impulse that starts this scene? What does your character want? What thought does that trigger? What action results?" Impulse-Desire-Thought-Action. Four simple questions. And something would click. The nervous ones found their footing. The confused ones found clarity. We'd run it twice — once to explore, once on camera. The improvement was often remarkable.

Here was a way to counteract the time pressure. Not a magic trick, but a framework that helped actors access what was already there. Even better, the resulting audition tapes were stronger, which helped sell my casting choices up the chain of command to producers and executive producers who hadn't been in the room.

Between directing jobs, I began running workshops at drama schools — East 15, Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, and Guildhall. My thinking was practical: if I could meet future acting talent before they graduated, I'd increase my own future casting options and be less dependent on casting directors. And it was good for the students too — someone with professional directing experience showing them what they'd be up against when they landed their first screen roles. Mutual benefit.

The format was simple: five days, two projects. First, soap scenes that looked simple but contained layers of subtext if you knew how to find them. Then complex feature film scenes with even more subtext to mine. Two practice runs in private before the real thing. And, for the first time, I applied the cycle to a workshop rather than just an audition.

Something remarkable happened. Over those five days, using the Impulse-Desire-Thought-Action cycle as our foundation, students transformed. Not just their technique — their confidence. By Day Five, watching playback of their feature film work — and more importantly, the edited scenes I'd managed to rough cut overnight — something shifted. We were getting the Ether effect: the raised awareness that comes from completing the cycle. Students would arrive on Day One uncertain about screen work and leave on Day 5 with genuine confidence that they could actually do the job they dreamt of doing.

Word got around. The Actors Centre asked me to run the same five-day workshop for their members — trained actors rather than students. It sold out immediately, and I was obliged to run several more in quick succession to meet demand. Clearly, there was an appetite from professional actors as well as students for this type of training. So I started running workshops independently under the title The Alchemy of Screen Acting, which has continued ever since — training over a thousand actors across twenty-five years.

But how did the cycle work? I could see the pattern, feel its rightness, but couldn't explain the mechanism. What actually happened when Impulse became Desire? How did Desire transform into Thought? What was the engine driving the change? The workshops succeeded, actors transformed, yet I was operating on instinct rather than understanding.

For years, I let the question simmer on the back burner while I concentrated on directing. The cycle worked — wasn't that enough? I had a career to maintain, productions to deliver, and actors to cast. The theoretical question could wait.

But it kept nagging at me. If I truly wanted to serve actors — not just to direct better performances but give them tools they could use independently — I needed to understand why the cycle worked, not just that it worked. The mechanism had to be there somewhere.

A 400-Year-Old Diagram

The answer came from a 400-year-old alchemical diagram, which I came across by chance. It appears in a 1660 French translation of The Twelve Keys of Philosophy by Basil Valentine, a Benedictine monk whose writings became foundational texts for European alchemy. The book's full title promises not just the Twelve Keys but also "the Azoth, or the means of making the hidden Gold of the Philosophers." That Azoth diagram (see the blog header image) - showing the seven stages of transformation arranged around a central face - appears in the second part of the book, and it changed how I understood everything.

The title page of the French edition of The Twelve Keys of Philosophy by Basil Valentine (dated 1660) and page 179 on which the V.I.T.R.I.O.L. diagram first appeared.

At the centre, the alchemist's face is surrounded by a seven-pointed star — representing the seven ancient planets and their corresponding metals. Around that, seven vignettes depict the seven alchemical operations. Then a circle containing the seven letters V.I.T.R.I.O.L. — an acrostic for the Latin phrase Visita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Invenies Occultum Lapidem: "Visit the interior of the earth; by rectifying, you will find the hidden stone."

Outside that circle sits an inverted triangle, its three points labelled ANIMA, CORPUS, and SPIRITUS. And at the four corners of the outer square, the alchemist's body connects directly to the four elements: his right foot stands on Earth (bottom left); his left foot on Water (bottom right); his left hand clutches a feather with a bird above it — Air (top right); and his right hand holds a flaming torch with a salamander — Fire (top left).

The four elements I'd been using for years — arranged in a cycle going anticlockwise around the diagram. But now I could see something I'd missed. That inverted triangle wasn't decoration. ANIMA, CORPUS, SPIRITUS — these were the tria prima, the three Principles that Paracelsus, the sixteenth-century Swiss physician-alchemist, insisted were fundamental to all transformation. Sulphur (the soul's passion), Salt (the body's fixity), Mercury (the spirit's fluidity).

ANIMA (Sulphur), CORPUS (Salt), and SPIRITUS (Mercury)

Look carefully at the bottom point of the triangle, where CORPUS sits. Around the cube representing Salt, you can see five small emblems arranged in a pattern — representing Earth, Water, Air, Fire, and the resulting Ether. The entire elemental cycle, depicted in miniature, suggests that this diagram shows how that cycle actually operates.

Five starlets representing: Earth, Water, Air, Fire and Ether

Then it hit me. Impulse doesn't simply become Desire. Something has to catalyse that transformation. Earth doesn't just turn into Water on its own, any more than ice spontaneously becomes steam without heat to drive the change. The three Principles weren't a separate system running parallel to the four elements. They were the missing mechanism. They were what made the four-element cycle actually work.

The stages had to be: Earth — One Principle — Water — Another Principle — Air — The Third Principle — Fire. Seven points, not four.

But which Principle catalyses which transformation?

Head, Gut, Heart

The translation became obvious once I saw it.

SPIRITUS/Mercury — the spirit, consciousness, mental fluidity, communication — that's the Head. Our thinking function. The part of us that analyses, plans, reasons, and perceives.

CORPUS/Salt — the body, physical manifestation, crystallised form, gut instinct — that's the Gut. Our doing function. The part of us that acts, moves, commits, grounds things in physical reality.

ANIMA/Sulphur — the soul, passion, emotional fire, the animating force — that's the Heart. Our feeling function. The part of us that loves, hates, desires, and fears.

The Three Intelligence Centres: Head, Gut, Heart

Head, Heart, Gut. These aren't just colloquialisms. Neuroscience has confirmed that we literally have three neural networks — three brains - complex webs of neurons that process information semi-independently. The brain, obviously. But also the heart, which contains around 40,000 neurons and sends more signals to the brain than it receives. And the enteric nervous system in our gut, containing over 100 million neurons, more than the spinal cord. The alchemists weren't doing abstract philosophy. They were mapping how human beings actually function.

So I could see that the tria prima corresponded to Head, Gut, Heart. But what was the order?

Think about any conscious creative process — writing a book, designing a building, planning an event. First comes Head: the thinking, planning, researching phase. Then Gut: the physical doing, the committed action that turns plans into reality. Then Heart: ensuring the project works efficiently and serves people well, the relational dimension that gives the work meaning.

So was the cycle Impulse-Head-Desire-Gut-Thought-Heart-Action?

No. That didn't quite fit.

The problem was that I was thinking about conscious creative processes — projects we deliberately plan and execute. But the Impulse-Desire-Thought-Action cycle isn't conscious. It's what happens beneath awareness, the hidden process that precedes every action we take. This is precisely why "actions reveal character" — because on screen, we can't see the internal journey that leads to the action. We only see its result. The character is revealed through what they do because there's no other evidence to go on.

And human psychology, operating at this subconscious level, is more complex than a simple linear sequence.

In real life, we don't process experience in a neat order — first Head, then Gut, then Heart. Going from Impulse to Desire involves both Head and Heart, and there's always a tension between them. When an impulse arrives — a piece of news, an opportunity, a threat — we feel something and we think about it, often simultaneously, often in conflict. The analytical mind says one thing; the passionate heart says another. They wrestle. They negotiate. Sometimes they align; sometimes one overrules the other. But both are always involved.

The diagram ultimately revealed the solution. CORPUS/Salt — the Gut — sits at the bottom point of the triangle, on what looks like a vertical axis. The Pillar of Salt. The fixed outer square holds the four elements in place — Earth, Water, Air, Fire, going anticlockwise around the perimeter. But within that fixed frame, the triangle PIVOTS on the vertical CORPUS axis.

If the triangle rotates on that Gut axis, then ANIMA and SPIRITUS — Heart and Head — would alternate positions as you move through the cycle. First one is prominent, then the other, then the first again. With Gut as the stable pivot point, grounding the whole process.

The Gut centre - “The Pillar of Salt” - the fixed axis of Body (CORPUS) around which the cycle of transformation rotates.

The true cycle revealed itself:

Impulse → Head/Heart → Desire → Gut → Thought → Heart/Head → Action

The slash marks aren't sloppiness — they're the key. Between Impulse and Desire, both Head and Heart engage, wrestling with each other. One may dominate, but both are active. Then Gut commits — crystallising desire into determination. Between Thought and Action, Heart and Head engage again, this time to align planning with passion. Then Action manifests.

Seven stages. Three intelligence centres. One mechanism. And now I understand not just that the cycle worked, but how.

Why Actors Get Stuck

Understanding the mechanism revealed something else — why actors get stuck.

The seven-stage cycle I've just described is the healthy pattern. Impulse flows through Head and Heart to Desire, grounds through Gut, rises through Thought with Heart and Head aligned, and manifests as Action. When this works properly, we experience it as flow, as authenticity, as being fully present. The three centres work together, each contributing its intelligence at the appropriate moment.

But it doesn't always work that way. Because everyone has a default centre.

Some people lead with Head. They analyse everything, plan obsessively, live in their thoughts. When an impulse arrives, they immediately start thinking about it — categorising, evaluating, strategising. Their Heart and Gut get bypassed or overruled. They know what they think but not what they feel. They understand situations but struggle to commit.

Some lead with Heart. They feel everything intensely, react emotionally, let passion drive their choices. When an impulse arrives, they immediately feel its emotional charge — excitement, fear, attraction, repulsion. Head and Gut struggle to get a word in. They know what they feel but not what to do about it. They experience life vividly but struggle to act strategically.

Some lead with Gut. They act on instinct, trust their physical responses, make snap decisions. When an impulse arrives, they're already moving — towards or away, fight or flight, in or out. Head and Heart come along for the ride. They know what to do but not always why. They act decisively but sometimes miss nuances.

None of these defaults is wrong. They're survival strategies, personality structures, ways of navigating the world that have served us well enough to get us this far. But they distort the cycle. The Head-dominant person might get stuck between Impulse and Desire — endlessly analysing, never committing. The Heart-dominant person might leap from Impulse straight to Action, skipping the Thought phase entirely. The Gut-dominant person might barrel through to Action without ever processing what they actually feel or think.

This is why actors get typecast. Not because of their looks or age — because their habitual patterns are dominated by their default centre. Casting directors unconsciously recognise these defaults. "She's great at vulnerable." "He does menacing well." "Perfect for the comic relief." What they're really seeing is an actor stuck in one configuration of the cycle, playing the same music in every role, just at different volumes. The Head-dominant actor intellectualises every character. The Heart-dominant actor emotes through every scene. The Gut-dominant actor physicalises every moment. Each is limited to roles that match their default — and shut out of roles that require a different centre.

The goal for actors, then, isn't to eliminate your default centre — that would be impossible and counterproductive. It's integration. Developing conscious access to all three centres so you can deploy them deliberately rather than defaulting unconsciously. An actor who can genuinely operate from Head, Heart, or Gut as the scene requires isn't at the mercy of habit. They have range. They can play characters whose default centre differs from their own.

But here's the crucial twist for dramatic storytelling: drama comes from dysfunction.

Compelling characters aren't integrated. They're stuck. They have a default centre that creates problems — for themselves and everyone around them. The detective who can't stop analysing (Head-dominant) and destroys his marriage through emotional unavailability. The lover who follows her heart (Heart-dominant) into disaster after disaster and wonders why she keeps getting hurt. The soldier who acts before thinking (Gut-dominant) and pays the price for his impulsiveness.

The actor's job is double: understand your own default pattern well enough to step outside it, while understanding your character's default pattern well enough to inhabit it truthfully. You need enough integration to have range, combined with the craft to portray specific dysfunction convincingly. That is the key to creating a three-dimensional screen character.

The seven-stage cycle gives you the map for both.

From Scene to Career

Here's where the system reveals its full power: the same seven-stage cycle operates at multiple scales.

At the mundane level, it describes how we process a single moment. An impulse arrives, Head and Heart engage, desire forms, Gut commits, thought plans, Heart and Head align, action manifests. This happens dozens of times a day, mostly unconsciously. For actors, this is the beat-by-beat level of scene work.

At the psychological level, the same cycle describes larger arcs of development. A project, a relationship, a phase of life. For actors, this is the level of character arcs across a screenplay.

At the archetypal level, the cycle maps onto the great patterns of transformation found in myth and story structure. The hero's journey. The three-act structure. For actors, this is the level of career and calling.

This fractal quality is crucial. What works for a scene also works for an act. What works for an act also works for a career. The same mechanism, operating at every scale.

And for screen actors specifically, this means understanding something uncomfortable but essential: in a highly competitive market, you absolutely have to consider yourself as a product. This doesn't mean selling out or becoming inauthentic. It means getting strategic about a career that won't manage itself. A career properly understood moves through three distinct phases, following a conscious creative process — each corresponding to one of the three intelligence centres:

Phase One: Product Identification (Head/Mundane)

Before you can market yourself, you need to understand what you're marketing. This phase begins with understanding the industry you want to join: why casting works the way it does, how decisions actually get made. Then acquiring basic screen acting skills — the craft foundation. Getting match-fit for the journey and staying that way. Understanding basic dramatic structure so you can break down any script. And accepting the absolute necessity of marketing in a profession where talent alone isn't enough.

Only then: discovering your screen type — not who you wish you were, but how the camera and the industry actually see you. And getting a headshot that matches that type precisely. This is analytical work requiring the Head centre's capacity for objective self-assessment.

Phase Two: Product Packaging (Gut/Psychological)

Once you've identified the product, you package it. Creating the requisite marketing tools: a CV that works, a showreel that demonstrates what you can do, a personal website that presents you professionally. Learning how to engage effectively with casting directors and agents. Understanding how to access production information so you know what's casting and where.

This is embodied work requiring the Gut centre's capacity for committed action. You're not just preparing materials — you're building the professional infrastructure that supports a career.

Phase Three: Product Placement (Heart/Archetypal)

Now you're ready to place the product in the market. Mastering screen audition technique so you can deliver under pressure. Networking authentically — building genuine relationships, not just collecting contacts. Learning how to deliver value on set so people want to work with you again. Understanding how to keep working once you've started. Eventually, as your centres integrate, transcending type to access a wider range of roles. And ultimately, giving back — helping those coming up behind you.

This is relational work requiring the Heart Centre's capacity for genuine connection.

Most actors get these phases catastrophically wrong. They jump straight to Phase Three — networking, hustling, trying to get meetings — before they've done Phase One (knowing who they are) or Phase Two (being camera-ready). They wonder why the meetings don't lead to work.

The answer is sequence. You can't package a product you haven't identified. You can't place a product you haven't packaged. The phases must be taken in order, like ascending spirals of development.

The Complete Map

The pattern I've described isn't my invention. It's been encoded in wisdom traditions for millennia — in alchemical diagrams, in mythological cycles, in the deep structure of story itself. I simply found a way to apply it to the specific challenges screen actors face.

Every properly constructed screenplay moves through three acts. Act One: departure from the ordinary world. Act Two: confrontation with challenges. Act Three: transformation and return. This maps directly onto our three phases: Head (understanding the situation), Gut (committing to the struggle), Heart (achieving meaningful transformation). Within those three acts, the same seven-stage cycle repeats at every scale — scene by scene, sequence by sequence, act by act. The fractal pattern that the alchemists encoded in their diagrams turns out to be the deep structure of all dramatic storytelling.

This is why Gerry Wilson's principle works. "Actions reveal character" isn't just good screenwriting advice — it's the natural conclusion of a seven-stage process. Every action emerges from an impulse that has been processed through all three intelligence centres. The action reveals character because it's the visible endpoint of an invisible internal journey. When the stages are authentic, the action rings true. When they're faked or skipped, the performance feels hollow.

Each of the three phases contains a complete seven-stage cycle. 7 × 3 = 21. The full journey from first impulse to sustainable career involves twenty-one distinct stages, each building on the last, each necessary for the next. The Alchemy of Screen Acting lays out all twenty-one in practical detail — the complete map I wish someone had handed me when I was starting out (so I could have applied the principles to my own directing career), the system that has transformed over a thousand actors in my workshops across twenty-five years.

"Actions reveal character," Gerry Wilson told me at film school. He was more right than either of us knew. Understand the seven-stage process behind every action, and you understand why some performances ring true while others feel hollow. You understand why some actors book roles while others, equally talented, never break through. You understand the hidden architecture of the craft — the alchemy that transforms raw talent into a working actor.

Twenty-one stages. Three phases. One mechanism.

This is the map. Now the journey is yours.

Andrew Higgs is getting his new book, The Alchemy of Screen Acting: Building a Sustainable Career in 21 Steps, ready for publication. Subscribers to Substack receive practical insights on screen acting and career development, and will be the first to know when the book becomes available. Subscribe for free using the link above.